Pierre Seel

Homosexuals were among the victims of the Holocaust. According to the Nazi’s own archives, between 1933 and 1945 over 100,000 lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people were arrested under paragraph 175 of the German Penal Code which- dare one say ironically?- condemned people for ‘committing acts against nature’.

More than 10,000 were sent to concentration camps, where a hierarchy of four groups was established: political adversaries, members of inferior races, criminals and ‘associates.’

Is it possible to consider certain forms of torture as more degrading to a human than others? According to the text before me, it is; and the most degrading tortures were reserved for the last and lowest of those groups fell lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people; female sterilisation, castration, scientific experiments which required subjects infected with typhus and malaria.

During the Second World War, the French government at Vichy passed a law to criminalise homosexuality, and after the war under Charles De Gaulle, legislation classed homosexuality as a ‘social flaw’ (in 1968, the World Health Organisation still classed homosexuality as a mental illness): it was not until 1981, when Francois Mitterand removed the legislative penalties, that the situation in this country improved.

Back in 1940, Pierre Seel was among a number of people arrested at a drag show in

Many years passed before Pierre Seel came forward: he was not the only French citizen deported on the basis of his sexuality to survive, but he was alone in speaking publicly about what he suffered. He fought to have the French authorities officially recognise the fact that he was deported for his homosexuality. He also fought with the organisers of commemoration services for the French deportees, who tended to overlook the fact that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people were among their number.

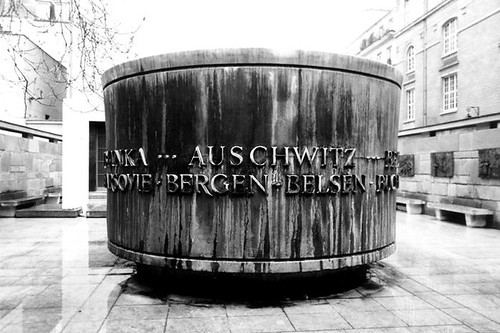

Unlike other cities like Berlin and Amsterdam, to this day France does not have a monument to commemorate those who were deported: in fact, it was not until 2002 that the pink triangle symbol used by the Nazi’s to distinguish ‘associates’ was added to the other triangles at the Holocaust monument on l’Ile de la Cite,

By speaking about his personal experience, Pierre Seel changed the way history has been rewritten. At a commemorative ceremony on 17th June 2006, public officials in the city of

Is it not also appropriate to commemorate in a different fashion? Something more permanent… and yet what is permanent in this ever changing world? Perhaps it is for each of us to determine how best to commemorate: one believes it is not so difficult to always carry a name in the back of one’s mind.

Monsieur Pierre Seel, a man who deserves remembering, don’t you think?

Deporte francais pour homosexualite

“I want others like me, who were deported for their sexuality, to be remembered;

to ignore, to forget, it is an acceptance of the Nazi’s crime”

No comments:

Post a Comment